Autism & Me—A First Person View Of Life As An Autistic Adult

Awareness of autism spectrum disorders has increased diagnoses, but not the public's understanding of what ASD is like for autistic adults.

April is World Autism Awareness/Acceptance Month, so we're revisiting my life—with updates—as an adult with autism spectrum disorder (ASD).

ASD is defined as:

"A serious developmental disorder that impairs the ability to communicate and interact."

"Autism spectrum disorder impacts the nervous system."

Back at the turn of the 21st century, autism rates "skyrocketing" made headlines.

Conspiracy theorists blame ASD on everything from atomic bomb testing to fluoride in water to vaccines to GMOs, but no peer reviewed, validated research supports any of their claims about the causes or for the increased diagnosis rates for ASD.

Unfortunately, that doesn't stop them from spreading misinformation.

ASD rates continued to increase in the 2000s, from 1 in 150 children diagnosed by age 8 in 2000 to 1 in 54 by 2016. The most recent data has the rate at 1 in 36 children.

That's almost 3% of the population, up from just 0.6% in 2000.

It might not seem like much, but when you consider Indigenous Americans are also about 3% of the U.S. population, you realize it's not insignificant either.

It's roughly 10.2 million autistic people in the United States.

Experts cite "improvements in diagnostic tools and education" as the most likely reason for increases. As late as the 1990s, autism was still considered a disorder exclusively found in boys.

With the acknowledgement that autism presents across genders, the rates naturally increased sharply.

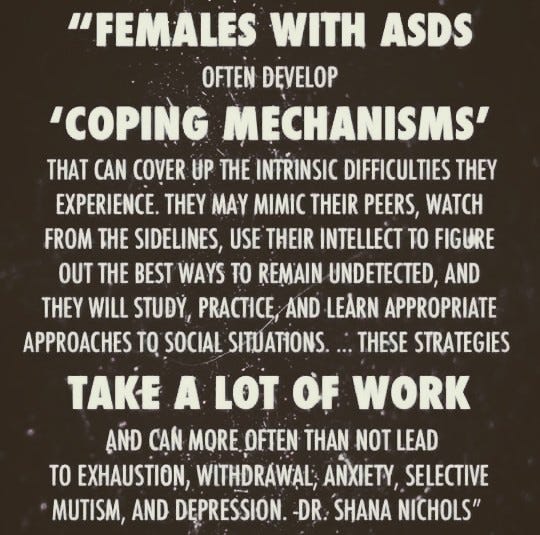

In the 2000s, many of the newly diagnosed are women in their 30s–60s. As children they were unlikely to have ever been evaluated for ASD.

I didn't get my autism diagnosis until I was 40-years-old.

Autistic Amelia

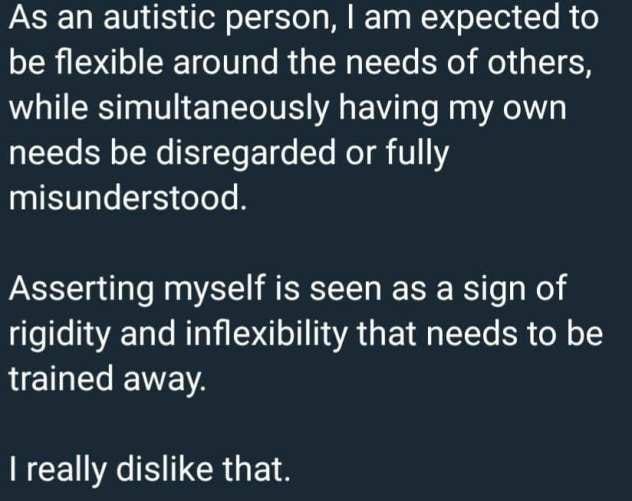

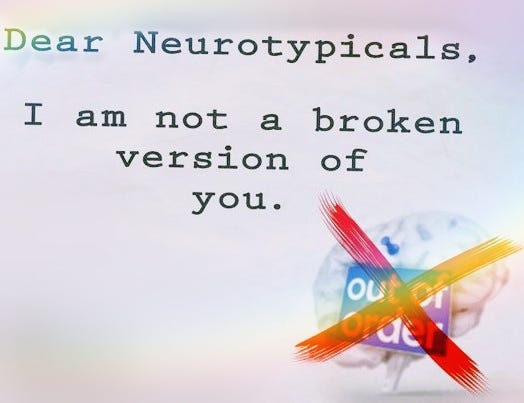

As an autistic human, it’s important to me to clear up some of the stigma created by toxic so-called advocacy groups that center on serving those who live or work with autistic people instead of actual autistic people.

They see us as defects to be fixed or eradicated, not people with disabilities to be reasonably accommodated.

The puzzle piece and the “wear blue” autism branding came from this type of advocacy group. That's why those symbols are rarely used by teens or adults with autism.

Instead, the neurodivergent infinity symbol is used by groups like Actually Autistic—an organization by, for and about autistic people.

The puzzle piece organization also advocates the use of a form of Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA), which forces children with autism to mask everything. Its goal is compliance and obedience not focused on the best interests of the autistic individual.

This controversial ABA has been criticized as abusive and traumatic and has negatively impacted the public's perception of all forms of ABA.

Autistic people were also labeled as high functioning—meaning verbal and largely able to integrate into the larger society—or low functioning—meaning nonverbal and/or unable to live independently.

But people with autism eschew these labels, as they're deceptive.

Our functionality is dependent on our environment. A "high functioning" individual can go nonverbal because of a loud noise, a smell, or fatigue disturbing their ability to mask.

High functioning means suppressing our autistic traits for the comfort of others. It's a learned behavior that is exhausting to maintain 24/7.

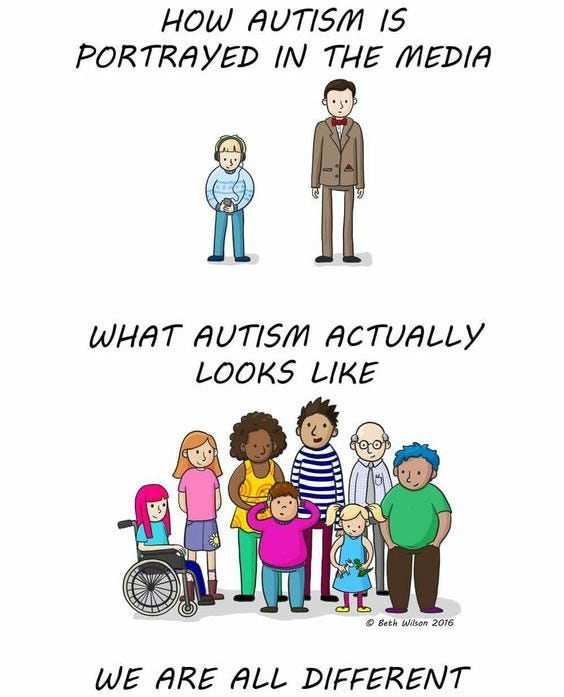

And there's a reason it's called the autism spectrum.

There are traits the public associates with ASD:

lack of eye contact and social awkwardness

fidgeting or stimming

repetitive motions or speech patterns

obsessive behavior

But just because it's common doesn't mean all people with ASD exhibit it.

Some autistic people trained themselves—or were forced—to mask these common traits.

What ASD Is Like for Me

Buckle up, folks—it's about to get weird.

I was completely nonverbal for about the first two years of my life.

According to my family, I didn't babble like most infants nor did I audibly cry very often. My Mother had my hearing and vocal cords evaluated multiple times as a result.

Then one day, shortly before my second birthday, I began speaking in complete sentences. No one in the family remembers my first words, but my Mother loved to tell people my second utterance.

I was sitting in a highchair by a table full of adults who all knew I was nonverbal. I joined the conversation at some point with a full sentence responding to something someone said.

It was a shock for everyone. I was asked why I hadn't spoken before.

My Mother said I replied:

"I never had anything to say before."

I don't have any memory of it, but the family swore it happened. Shortly after I started speaking at age 2, my Mother taught me to read.

Prior to that, I was labeled developmentally disabled—like most girls with autism in the early 1970s.

I don't experience hunger or thirst.

After discussing losing weight with my primary care doctor, she suggested I eat only when hungry. I've always had a tendency to forget to eat, so I had alarms on my phone to remind me.

I turned off all my reminders then forgot to eat for 6 days.

Lack of hunger and thirst are common traits reported by autistic people. The thing in your brain or body that tells you you're hungry or thirsty either malfunctions or simply never existed in our brains.

Studies found the idea a child will automatically ask for food when hungry doesn't work with many autistic infants and can lead to failure to thrive.

When I do remember to eat, it is often late at night as a memory function, not physical discomfort caused by hunger. I forget to drink as well, but it's easier to remember because my lips or mouth get dry.

I've been labeled a super taster, hearer and smeller.

My ability to detect tastes, sounds, and scents others don't pick up on has put me in a class labeled “super.”

Wow, how great is that‽

It isn't.

Super taster and sophisticated palate aren't the same.

The unusual things I taste aren't the nuanced flavors chefs want people to experience. I taste some of the minerals, additives, fillers, colorings and chemicals naturally occurring or added to our foods and beverages.

Artificial sweeteners are the worst. I don't taste sweet with aspartame—I taste petroleum chemicals.

I have a very low chili pepper tolerance. Mild to other people is extremely spicy to me and too much spice results in pain, vomiting or decreased consciousness.

In a “silent” room, I hear the gurgling of water in the plumbing and the hum of electricity in the wiring. I keep a fan running 24/7/365 to mask those sounds.

Hearing electricity is a very common phenomenon among autistic people. So if you're ASD diagnosed and hear a humming sound no one else does, you aren't crazy.

Smells are perhaps the worst for me.

Organic or biological smells that sicken others smell strong to me, but don't bother me. For example, I like the smell of skunks.

But manufactured scents like most perfumes, body sprays and household cleansers induce migraines, vomiting or loss of consciousness.

I have a sommelier friend who extracts, distills, ages and blends organic materials—flowers, fruits, vegetables, plants, soil, wood resins, etc...—to create perfume. Rachel's award-winning creations don't bother me at all, unlike the expensive mass-produced chemical cologne concoctions.

I don't know if my reactions to naturally occurring versus manufactured scents is a common autistic trait or unique to me. I've been unable to find any research on the phenomenon.

I don't experience pain like neurotypical people.

I once fell on the ice in spectacular fashion and heard some cracking noises. I then realized the lump under my back was my left foot and not a rock or ice.

I drove myself to the ER and walked in unaided. They told me in addition to several sprains, strains and bruises, my foot was broken.

I likely injured myself further because of the lack of pain.

I've had gallstones and kidney stones and both are described as excruciatingly painful, but I only felt some pressure and muscle spasms. My gallbladder was necrotic before I knew I had a problem.

But as noted previously, spicy foods and certain sounds or smells can cause me extreme pain.

Neurotypical people have told me everyday tastes, sounds, and smells aren't usually physically painful.

Medications work in unusual ways with my brain chemistry.

I'm deathly allergic to prednisone, which is often used to treat allergic reactions. I've been characterized by anesthesiologists as "very difficult" to anesthetize.

I have bad reactions to drugs that rarely have side effects. A new medication is always a carefully monitored risk.

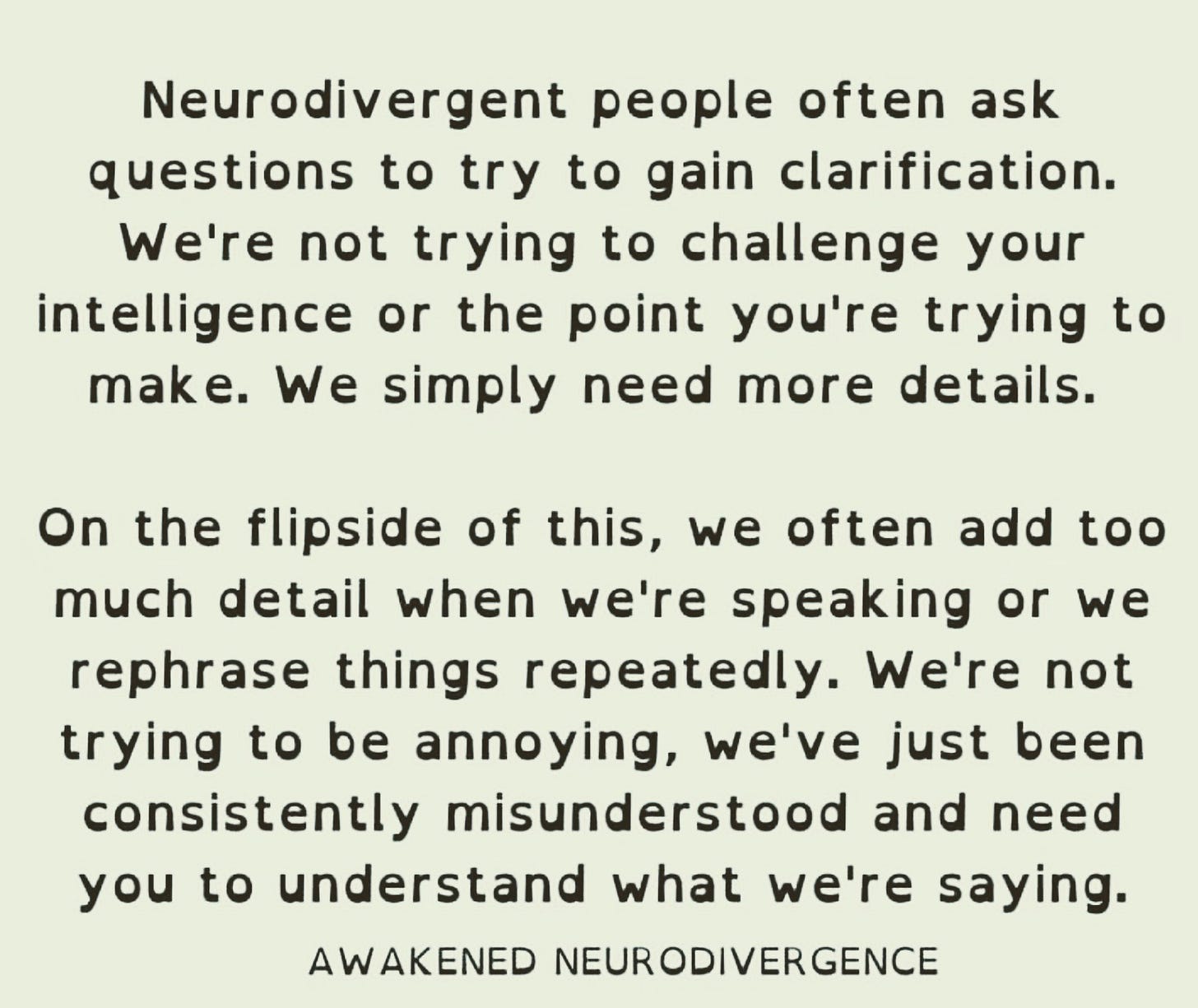

If I say or write something, it's been meticulously crafted to express my exact meaning.

Reading between the lines to get what a person really means baffles me. Why not say exactly what you mean?

I struggle with people’s assumptions that everyone communicates this way.

I find people reinterpreting my exact words to mean something else very hurtful.

As neurodivergent Twitter user "lazy perfectionist" put it:

"neurodivergents often feel the need to clarify things hours/days after they said it because we grew up being constantly misunderstood & getting in trouble for miswording or being too blunt & can't stand the thought of people misunderstanding what we actually mean."

"we can often over-explain or 'not let something go' because we are so often misunderstood and want to eliminate any chance of that happening again."

"it's frequently a trauma response stemming from chronic ridicule and punishment after being misinterpreted."

I don't hint or drop subtle clues.

I either say something directly or say nothing.

My direct nature can be very off-putting for people used to the little white lies, doublespeak, and passive-aggressive nature of their own communication.

I think in absolutes, but not how most people assume.

Seemingly simple questions—what's your favorite color?—are impossible for me to answer and induce anxiety. It’s an absolute question requiring one favorite.

But I can't respond with one because I like different colors for different things—clothes, cars, house paints, decor, etc....

I also struggle with most standardized psychological testing.

If it asks "Do you..." and I have done it even once in my life, the answer is "yes." But the analysis assumes my answer reflects tendencies, not one isolated incident.

I have near total recall.

They call it an eidetic memory now, but it means I remember the interaction I had 12 years ago as clearly as the one I had 12 minutes ago.

So time doesn't lessen hurt feelings for me.

I'm more likely to tackle an issue to get immediate resolution because I’m unable to forget the hurt. I also obsess over mistakes I made when I was 15 years-old as much as ones I made 15 minutes ago because the two memories are equally vivid.

I'm leery of interacting and developing close relationships for fear of making mistakes that most people will easily forget or never notice. I also struggle to trust people because they remember what they meant or wanted to say or do, not their actual words or actions.

I spend more time observing than interacting with people because of this.

I have dysphasia.

Aphasia has made the news lately because of actor Bruce Willis' diagnosis. Aphasia is a loss of communication skills due to illness or injury that can get worse depending on the cause.

Dysphasia presents the same challenges, except a person is born with it and it is less likely to get worse. Both conditions affect a person's ability to express and understand written and spoken language.

I will pause mid-sentence because I cannot access the right word. Tricks that help me recall words are snapping my fingers or looking up to the ceiling.

The stilted speech pattern and physical tricks I use can be confusing or off-putting for others.

When I'm tired or ill, my dysphasia gets worse, affecting my speech and ability to read and write.

I have mild prosopagnosia (face blindness).

I got my ASD diagnosis—called Asperger's Syndrome at the time—as part of a Dartmouth Medical School study on the connection between prosopagnosia and Asperger's.

The childhood friend who recommended me for the study had such severe face blindness he couldn't recognize his own parents. Mine is very mild in comparison, but it still leads to misunderstandings.

I usually don't acknowledge people I know when we cross paths unexpectedly, because I don't recognize them.

I have to examine a face far longer than it takes the average person, so I'd have to creepily stare at strangers in order to identify the people I know.

I never recognize people driving by unless I know their car. I’ve failed to recognize even family members.

But people assume I’m just rude or ignoring them.

My temperature gauge is broken.

In the summer of 2023 when everyone was complaining about the extreme heat, my body recognized it was hot but my brain didn't. I was sweating at appropriate levels for the temperatures, but I didn't feel hot.

If I hadn't been drenched, I would have been completely comfortable.

Then in winter, I didn't get cold.

At one point, a storm knocked out one of the furnaces in my building. I only knew because my landlord came to update me on repairs and apologize for the cold temperatures.

I was wearing just a t-shirt and leggings and he asked me “Aren't you cold?”.

I checked the thermometer afterwards and it was 43°F (6°C) in my home. My skin felt cold to the touch when I placed my hand on my arm, but I didn't feel cold.

I invested in several room thermometers after that incident.

I now know I can't trust my brain to tell me it's dangerously cold. Hypothermia is a distinct possibility after prolonged exposure to temperatures below 40°F (4°C).

Most important for people to know is I can't turn it off.

I can't turn off any of it. There's no mind over matter solution—my ASD reactions will always be there.

I’ve learned masking skills to blend into society, but when I'm overtired, sick or medicated, my mask slips.

I was labeled “high functioning” socially because I forced myself to work in highly social situations like retail and customer service phone lines.

But I'm still autistic.

I still have occasional meltdowns.

Autistic children become autistic adults. Our atypical reactions to stimuli never go away.

But we can learn tools to help us cope.

And society can learn that what gets labeled "normal" is just more common, not a universal truth.

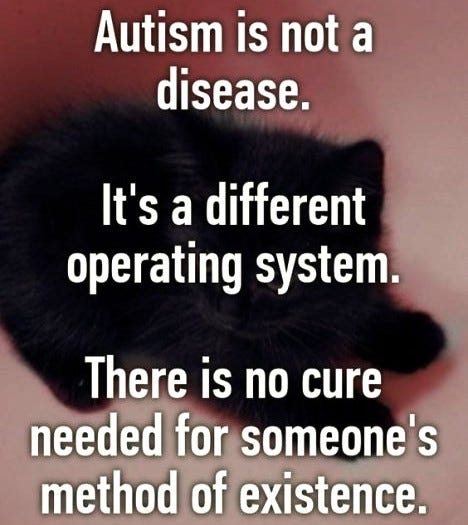

Would I rather be neurotypical?

No. Autism works for me. I don’t want a “cure.”

What I'd like is for people to recognize we exist and if they have questions about autism, we’re the experts.

Speak to us, learn about our experiences.

The one trait we all share—neurotypical and neurodivergent—is the desire for acceptance and understanding.

~~~~~~~~~~