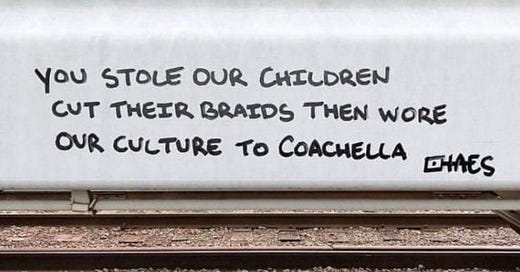

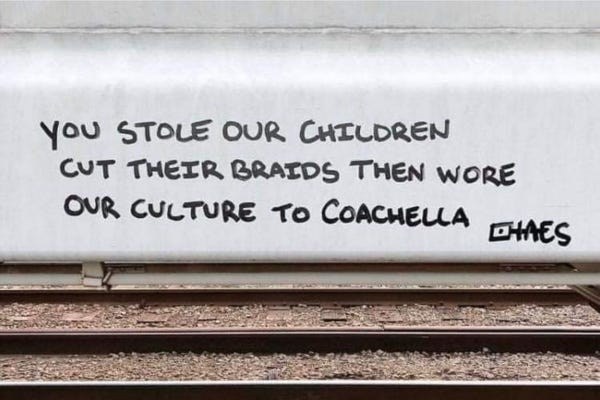

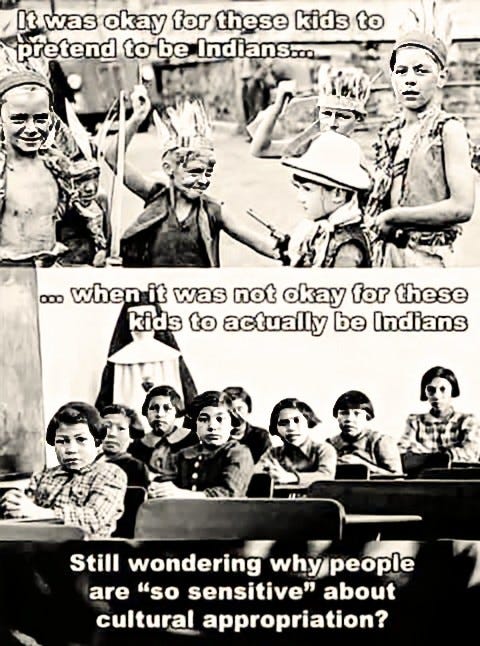

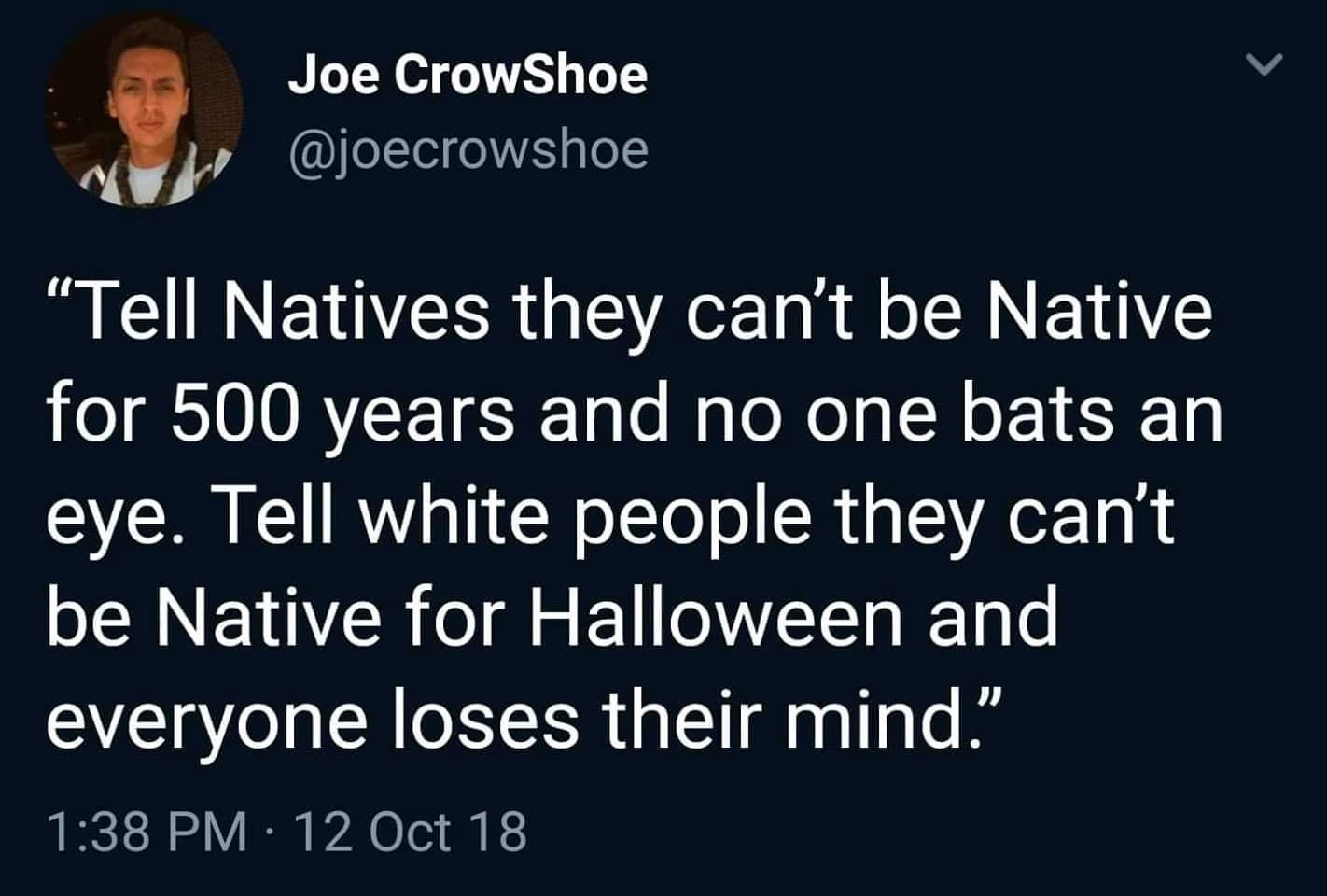

It wasn't until the 1970s that Congress finally passed several laws making existing as an Indigenous American in the United States no longer illegal. Indigenous language, religion, dance, and other aspects of our culture were banned by a series of federal laws generally referred to as the Assimilation Acts.

Indigenous North American culture was illegal for Indigenous peoples to practice in the United States, but A-OK for the Boy Scouts to steal to play “Indian.”

So, yes.

We're still a bit salty.

The large feathered headdress—a.k.a. war bonnet—has become an almost universally recognized symbol of “Native Americans.” However it should not be.

Why?

Only some of the tribes that lived on the Great Plains of the present day United States and Canada created and wore the elaborate headdresses. And outside the Great Plains, no tribes made or wore them.

There are 574 federally recognized tribes in just the United States. So more tribes never wore the Plains style headdresses than the number that actually did.

Each of those individual tribes is distinguished by their own traditions, adornments, homelands, etc...

Associating all Natives with the Plains style headdress is something called homogenization. North America is a large land mass. Thousands of tribes of people lived in what is now Mexico, the United States, and Canada.

While people recognize a person from Germany and a person from France—relatively small countries that share a partial border—do not look the same, traditionally dress the same, nor all speak the same language, many people think all Indigenous people from North America looked, spoke and dressed the same.

We did not.

When people are homogenized, less care is given to their unique cultures. Homogenized people are dehumanized or seen as less than people who maintain a strong cultural identity.

So while headdresses have become a universal symbol, it is not a universal cultural artifact. When you ask a Native friend if it is OK to wear a headdress, unless their tribe's traditions included headdresses, their opinion is as relevant as asking a person from Mongolia or Portugal for their opinion.

My Maternal side, the Kanien'kéhà:ka of the Haudenosaunee and Metís, did not wear the elaborate Plains style headdresses.

Women wore adorned caps or headbands. Men wore bands with a variety of feathers that stuck straight up, roaches made of porcupine hide and hair, or turkey feather caps.

My Paternal side, Plains tribe the Oglala Lakȟóta of the Očhéthi Šakówiŋ, did wear the elaborate eagle feathered headdresses.

But even as a pipe carrier and person who performs ceremony in my Father's traditions, I cannot wear a headdress.

But it is not because I am a woman.

A headdress is earned.

It is not a hat.

It is not for "men only."

Veterans who have distinguished themselves in battle or great leaders who the tribe wishes to honor earn the right to wear a headdress. My Great-Grandfather Matȟó Hintȟó (Roan Bear) earned his headdress at age 15 at Pezí Sla Wakapa—the Battle of the Greasy Grass or Little Bighorn for non-Lakȟótas.

My Até Ralphie* (Uncle Ralphie) inherited Matȟó Hintȟó's regalia including his headdress. As a military veteran, he and my Até (Father) could wear the headdress.

Mičiyé (older Brother) Rick inherited the regalia as the Čhaské (oldest son) and a military veteran. They and the rest of my siblings through Até Ralphie decided to donate the regalia to a museum.

*In both Lakȟóta and Kanien'kéha:ka kinship, the Brothers of your Father are also your Fathers. The Sisters of your Mother are also your Mothers. Their children are your siblings, not your cousins. My Akenistén:’a (Kanien'kéha for Mother) had two Sisters. My Até had one Brother. I have three Mothers, two Fathers, and 17 siblings.

My Sister's owirá:'a or wákáŋyéja (Kanien'kéha and Lakȟótayapi words for child) is my child and I am their Akenistén:’a or Ina (Kanien'kéha and Lakȟótayapi words for Mother).

The Sister(s) of your Father and Brother(s) of your Mother are your Aunties and Uncles,but so are others who share kinship with your parents. Their children are your cousins. I have hundreds of Aunties, Uncles, and cousins.

The Lakȟóta woman in the photo below, Minnie Hollow Wood, also earned her headdress at Pezí Sla Wakapa—where a US Army regiment lead by George Armstrong Custer attacked the summer camp of allied bands of Lakȟóta, Dakota, Arikara, Northern Cheyenne and Arapaho .

In 1876, Minnie distinguished herself when fighting against the U.S. cavalry and was awarded the right to wear a war bonnet.

By 1877, she was among the prisoners at Fort Keogh in what is now Montana. She and her husband—Cheyenne Chief Hollow Wood—were later transferred to The Northern Cheyenne Indian Reservation where they lived the rest of their lives.

Our headdresses are sacred to us.

They are not toys or costumes or hats.

If you have not earned one, you cannot wear one.

PERIOD.

Thank you for this history and the clear explanation 💗

I am so sorry that so many of us white people ever did, and still do, treat you so horribly, and with such disrespect.