My Early Lesson In Racism And Hypocrisy

Picture it. Little Rock, Arkansas, 1975. A young Indigenous girl is about to get a reality check.

I began school in 1975 in Little Rock, Arkansas because my Father was retiring as a Chief Warrant Officer in the United States Navy to go to work as a nuclear power plant inspector for the Nuclear Regulatory Agency.

After almost 10 years of marriage where my Father was mostly at sea as a nuclear technician on battleships and destroyers, my parents were finalizing a divorce on foreign soil.

Mum's people are from Canada and she was born there, but she grew up in northern Maine after her maternal Aunt Amelia—yes, that's where I got my name—and Uncle Linwood Cowett adopted her after her mother's death when she was 3.

My Father was born and attended mandatory boarding school on Pine Ridge Reservation, but was enrolled at Rosebud Reservation. Both are in South Dakota.

So, foreign soil as our family had zero ties to Arkansas or the South, unless you count my Father's latest paramour.

My Father filed for divorce—and retired to Arkansas—at the request of said girlfriend.

As a devout Catholic my Mother would never have filed for divorce despite my Father's utter inability to honor his wedding vows. But the divorce was a blessing because it kept my Mother out of jail and my Father out of a casket.

Turned out absence didn't make the heart grow fonder but it had kept my Mother from asking me to help hide a body.

My Mother and I had an interesting relationship.

My Father was a well-meaning, mostly harmless narcissist. He didn't disregard other people's thoughts or feelings intentionally—he just never realized anyone else had any.

He was brilliant but with the emotional maturity of a toddler. He responded best to strict, strong women.

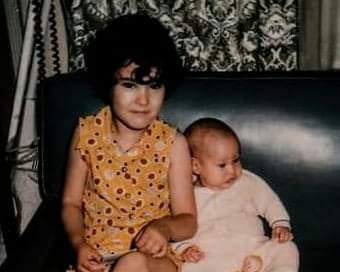

My Mother was made of iron with the added bonus of undiagnosed, untreated bi-polar disorder for most of her life. My parents had three daughters by 1975—Helena age 8, me almost 6 and Jacqueline age 7 months.

Mum had no desire to take care of a fourth child that was 36 years old and unlikely to ever grow up. Papa was rightfully terrified of Mum which is probably how he survived long enough to get a divorce.

By 1975 he was also learning to fear me. I'm my Mother’s daughter, except with autism spectrum disorder added and all of her bi-polar disorder removed.

We were an intimidating pair when we teamed up and vicious when we clashed, even then.

Anyway…

Arkansas—the “state my Father dragged us to so he could start his new career only to file for divorce once we were stuck there”—didn't have public school kindergartens yet. So I began with 1st grade at age 5.

I had already learned to read, write, add and subtract at home before beginning school. Unfortunately most of my classmates had not because, no kindergarten.

This is almost 48 years ago but I remember it all vividly. Of course it helps that I inherited a near eidetic memory from my father's side of the family.

Mandatory busing to force reluctant states to desegregate schools was in full effect, so classes were “racially proportioned.”

In Arkansas that meant rich kids went to segregated, Whites-only private schools that did have kindergarten and public schools ensured the busing program was as inconvenient as legally possible for students and parents to spite the federal government.

My sister and I and kids from grade 1-12 rode a bus for 2 hours every morning to get to the massive Little Rock school complex. We all lived in the same massive trailer park that was probably more populated than the small town in Maine we would move to—Ashland.

The trailer park was in the city limits of Alexander, Arkansas and assumed to be exclusively White which was the reason every child from the park was bussed to Little Rock to a school that was definitely more populated than Ashland, Maine.

I was in one 2-story building of just grades 1 and 2 and Helen was in another bigger building far enough away the bus had to take her there where grades 3-5 were. Grade 6 through 8 had another building further away then eventually you got to the high school.

After school it was another 2 hours to get home. Our racially proportioned school put only two Black students—one girl and one boy who actually lived in Little Rock—in each classroom.

Everyone else harvested from surrounding rural towns and suburbs was supposed to be White.

I don't know about every classroom, but in mine the two Black students were required to sit in the outside corner desks in the last row so they couldn't talk to each other or disturb any other students. It also put them the furthest from the teacher.

Our teacher, Mrs. Rainey had been teaching for years in what I now realize were segregated, Whites-only schools. She was in her late 40s or early 50s with a giant pile of frosted blond hair on her head.

A few years later the character Flo on the sitcom Alice would remind me of her.

She called me her special darlin' and was always calling on me for special projects or special recognition. She was constantly bragging about my abilities to the other teachers, the principal, students, parents and always complimenting me.

I adored her.

My best friend in class was a girl named Marie. She was funny and very intelligent and confident for our age.

She spoke her mind and always made me laugh.

I loved spending all of my time during recess with Marie, although I rarely got to spend time with her during classes. And for some reason Marie was never invited to any of the after school groups or birthday parties.

One day in early spring Mrs. Rainey had lunch recess duty—she normally never had any recess duty because of her seniority. After recess she asked to speak to me in the hallway before entering our classroom.

She told me she noticed I had spent recess with Marie. I told her Marie was my best friend in the whole world.

She smiled and said since I wasn't from Arkansas (Yankee! although I had moved to Arkansas from Nebraska) I probably didn't understand it wasn't right for me to play with Marie.

I was shocked and asked:

"But why? I really like Marie.”

"Well, darlin', Marie is colored. Good little White girls like you don't have colored friends."

I actually laughed.

"Oh, it's OK then. I'm not White."

Mrs. Rainey got white(r), turned around, went into the classroom and closed the door in my face.

She came back out, handed me a note and said, "Go to the principal's office,” then turned on her heel and went back into class, closing the door behind her.

I went to the office, handed my note to the secretary, who told me to sit and wait. When it was almost time to go home—2 hours by bus and not much faster by car as most of us were picked up at the same stop—my mother arrived.

We went into the principal's office.

He looked very, very upset when he seethed:

"Ma'am, your daughter told her teacher that she is not White. Is this true?"

"Yes."

"So what are you people then?"

Mum paused a tick before replying:

"Human. You?"

Mum never suffered fools gladly.

I thought the guy’s head would explode.

He replied in an increasing volume:

"Ma'am, you could quite possibly be breaking several laws by misrepresenting yourself as Whites. You do know about the busing laws don't you?”

“We have to know what RACE you people are! You have a child in 4th grade also. Both girls may be suspended until this is sorted out."

Mum, in the same even tone, replied:

"We never said we were White and you all never asked. You all just assumed we were when I enrolled them.”

“We're Native."

In what I now know is called being apoplectic, he bellowed:

"Native what!"

With a raised brow Mum asked:

"Remember the people that were here before the White people showed up?"

Him, exasperated:

"So you're Indian."

Mum, toying with her victim:

"No.

“Indians come from a country called India in South Central Asia. We're all from the United States."

That part actually wasn't 100% true since Mum was born in Canada, but the Haudenosaunee Confederacy stretches across the current border so...

Seeing an escape, he responded:

"I'll have to talk to the superintendent about this. Your children may not be able to return to this school."

Having had her fun, Mum said without an ounce of sincerity:

"Well, that would be a real shame.”

“I'm leaving now. You know how to get in touch with me."

And we got up and left.

This was Mum's second encounter with Principal Anger Management Issue. On the first day of school Helen and I had to wait in our respective principal's offices because Mum failed to sign the mandatory corporal punishment approval form.

In 1976 in Little Rock, Arkansas, elementary school principals made it mandatory for parents to give an adult male their blanket permission to beat their child with a wooden paddle that looked like a cricket bat.

I know because the principal carried it from room to room on the afternoon of our first day of school to make sure we all knew what would happen if we didn't “behave.”

Mum got tag teamed by both principals. She refused to sign, they threatened expelling us, Mum was unfazed and they weren't allowed to touch us.

Like I said, Mum was formidable.

I knew Mum was pissed, but I wasn't sure exactly what had happened other than I told the truth and everyone—which for a 6-year-old meant my teacher and principal—freaked out.

Mum didn't speak to me on the way to go get Helen—who had also been pulled out of class for being secretly not White—nor on the way home while Helen and I sang along to the radio.

When we got home Mum told us to go outside and play.

That evening she told me the school had called. Apparently they were short on Natives in their school system, so they not only wanted us back, they needed us.

So I went to the same school the next morning and continued to play with Marie every day.

The only difference was Mrs. Rainey never spoke a word to me again.

If I raised my hand she'd ignore it. If I spoke to her she pretended not to hear.

I told Marie about it a few weeks later and asked her what was wrong. She explained I needed to decide if I was going to pretend to be White from now on or not. I told her I didn't want to be White, I wanted to be me.

She laughed and said:

"You better get used to being treated this way then. It's called racism. She don't like you no more because you ain't White."

Confused, I responded:

"But I was never White. I never said I was White."

Marie explained:

"Yeah, but she thought you were. That's why she's so mad. She liked you, a lot, and she's probably never liked anyone who wasn't White.”

“There's nothing they hate worse than finding out we're just as good as they are. Or even better."

We moved to Northern Maine that summer—back to my Mother’s small hometown—when my parents’ divorce became final.

I never saw Marie again but I wonder what happened to her. Looking back she was so wise and wonderful at that age. I hope she had a great life.

And I wonder what happened to Mrs. Rainey.

Did she keep her hate for the rest of her life?

I know I learned a lot from the experience.

I hope maybe some small part of her did too.

A remarkable story, so well told...

What a wonderful article. Thank you for sharing your story.